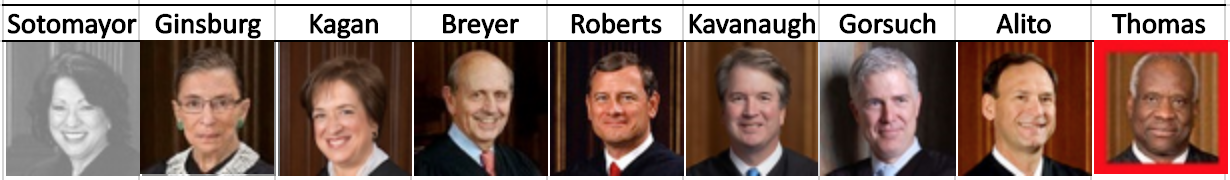

In a narrow opinion, the U.S. Supreme Court held yesterday that a Kansas police officer had reasonable suspicion to stop a vehicle about which he knew nothing more than that its registered owner had a revoked driver’s license. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the court in Kansas v. Glover; Justice Elena Kagan wrote a concurrence stressing the narrowness of the decision, which was joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Justice Sonia Sotomayor was the lone dissenter.

On April 28, 2016, Douglas County Deputy Sheriff Mark Mehrer was on routine patrol when he saw a 1995 Chevrolet 1500 pickup truck and decided to run its plate number through the Kansas Department of Revenue database. According to the database, the truck was registered to Charles Glover Jr., who had a revoked Kansas driver’s license. Mehrer stopped the truck, which was indeed being driven by Glover. Glover was charged with being a habitual violator, but the Kansas Supreme Court ultimately upheld his motion to suppress the evidence resulting from the traffic stop on Fourth Amendment grounds.

What made this case unusual was that there were no witnesses at trial. Instead, the trial was based on a short stipulation of facts stating that Mehrer assumed the truck was being driven by the registered owner, that he did not observe any traffic infractions and that he did not attempt to identify the driver.

In reversing the Kansas Supreme Court, Thomas’ majority opinion stated that “the Fourth Amendment permits an officer to initiate a brief investigative traffic stop when he has a particularized and objective basis for suspecting the particular person stopped of criminal activity.” The majority stressed that this “reasonable suspicion” standard is far less exacting than another Fourth Amendment standard, “probable cause.” Reasonable suspicion “depends on the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act,” wrote Thomas. The standard permits officers to make “commonsense judgments” — it does not require them to achieve “scientific certainty.”

The deputy knew that the registered owner of the truck had a revoked license and that the model of the truck appearing in the database matched the observed vehicle. “From these facts,” wrote Thomas, “Deputy Mehrer drew the commonsense inference that Glover was likely the driver of the vehicle, which provided more than reasonable suspicion to initiate the stop.”

“We emphasize the narrow scope of our holding,” stated the majority. “The [reasonable suspicion] standard takes into account the totality of the circumstances. … As a result, the presence of additional facts might dispel reasonable suspicion.” For example, wrote Thomas, if the registered owner is a male in his 60s, and the officer observes that the driver is a female in her 20s, then the totality of the circumstances would not provide reasonable suspicion. According to the factual stipulation in this case, however, Mehrer was unaware of anything suggesting that the driver was anyone other than Glover, and the majority made it clear that Mehrer had no duty to try to get a better look at the driver in order to get any “additional facts.”

The majority also noted that Kansas law “reinforces that it is reasonable to infer that an individual with a revoked license may continue driving.” This is because in Kansas, a driver’s license can only be revoked (as opposed to merely suspended) when the driver has “demonstrated a disregard for the law or [is] categorically unfit to drive,” according to the court. A Kansas driver’s license “shall” be revoked on the basis of convictions for involuntary manslaughter, vehicular homicide, battery, reckless driving, fleeing or attempting to elude a police officer, or “a felony in which a motor vehicle is used.” A license “may” be revoked for frequent, serious traffic offenses indicating disrespect for traffic laws and the safety of other persons; three or more moving violations within a 12-month period; incompetence to drive; conviction for a moving offense while one’s driving privileges were restricted, suspended or revoked; violating license restrictions; being under house arrest; or being a “habitual violator.”

This list of reasons for license revocation is important, stressed Kagan’s concurring opinion, because it relates to the registered owner’s “proclivity for breaking driving laws.” If Glover’s license had merely been suspended, or if Kansas had been one of the states that permit the revocation of driver’s licenses based on simple failure to pay license or court fees, the officer would not necessarily have had reasonable suspicion, wrote Kagan. The majority, although agreeing that the Kansas license revocation scheme “lend[s] further credence to the inference that a registered owner with a revoked Kansas driver’s license might be the one driving the vehicle,” stopped short of agreeing with the concurrence that it was a decisive factor.

In dissent, Sotomayor asserted that the majority “has paved the road to finding reasonable suspicion based on nothing more than a demographic profile.” The majority responded that existing precedent allays this concern. “Traffic stops of this nature do not delegate to officers ‘broad and unlimited’ discretion to stop drivers at random,” the court stated. “To alleviate any doubt,” Thomas continued in a footnote, “we reiterate that the Fourth Amendment requires … an individualized suspicion that a particular citizen was engaged in a particular crime. Such a particularized suspicion would be lacking in the dissent’s hypothetical scenario, which, in any event, is already prohibited by our precedents.” He then cited the court’s 1975 decision in United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, which found that the Fourth Amendment was violated when an officer stopped to question a vehicle’s occupants about immigration status solely on the ground that they appeared to be of “Mexican ancestry.”

All three opinions spent time on the relationship between “common sense” and expertise, with differing conclusions. Sotomayor’s dissent interpreted precedent as recognizing a common-sense approach made up of “the perspectives and inferences of a reasonable officer viewing ‘the facts through the lens of his police experience and expertise.'” The majority disagreed, saying that “[n]othing in our Fourth Amendment precedent supports the notion that, in determining whether reasonable suspicion exists, an officer can draw inferences based on knowledge gained only through law enforcement training and experience. … The inference that the driver of a car is its registered owner does not require any specialized training; rather, it is a reasonable inference made by ordinary people on a daily basis.”

Kagan’s concurrence expressed skepticism that common sense could support the assumption in Glover’s case that the registered owner was driving the vehicle. “When you see a car coming down the street, your common sense tells you that the registered owner may well be behind the wheel,” she wrote. “Now, though, consider a wrinkle: Suppose you knew that the registered owner of the vehicle no longer had a valid driver’s license. That added fact raises a new question. What are the odds that someone who has lost his license would continue to drive? The answer is by no means obvious.” Without everyday experience of this particular wrinkle, “Your common sense can … no longer guide you.”

As with most narrow decisions, the unanswered questions beg attention. Kagan’s concurrence raised three interesting factual permutations. First, she asked, what if “a car bears the markings of a peer-to-peer carsharing service,” such as Uber or Lyft? Second, is the assumption that the license-revoked registered owner is driving as supportable when the vehicle is a minivan as when the vehicle is a Ferrari? Third, suppose the officer has a consistent record of stopping vehicles for illegitimate reasons, or at least stopping an unusually high percentage of vehicles being driven by someone other than the license-revoked registered owner? “The balance of circumstances may tip away from reasonable suspicion,” Kagan stated.

Still another question is what future defendants could do to disprove the existence of reasonable suspicion. “If the State need not set forth all the information its officers considered before forming suspicion,” asked Sotomayor in dissent, “what conceivable evidence could be used to amount an effective challenge to a vehicle stop? Who could meaningfully interrogate an officer’s action when all the officer has to say is that the vehicle was registered to an unlicensed driver?”

But the majority rejected the dissent’s interpretation of its approach. “The dissent argues that this approach impermissibly places the burden of proof on the individual to negate the inference of reasonable suspicion,” the court stated in a footnote. “Not so. … [I]t is the information possessed by the officer at the time of the stop, not any information offered by the individual after the fact, that can negate the inference.”

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, is among the counsel to the respondent in this case. The author of this post is not affiliated with the firm.]

Recommended Citation: Evan Lee, Opinion analysis: Court upholds stop of vehicle based entirely on registered owner having revoked license, SCOTUSblog (Apr. 7, 2020, 10:30 AM), https://ift.tt/3aUhS8E

"Opinion" - Google News

April 07, 2020 at 09:30PM

https://ift.tt/3aUhS8E

Opinion analysis: Court upholds stop of vehicle based entirely on registered owner having revoked license - SCOTUSblog

"Opinion" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2FkSo6m

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment