Today the Supreme Court ruled, 6-3, that the Clean Water Act requires a permit when a point source of pollution adds pollutants to navigable waters through groundwater, if this addition of pollutants is “the functional equivalent of a direct discharge” from the source into navigable waters. Because the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit applied a different legal test in determining that a permit was required for a sewage treatment facility operated by the County of Maui, the Supreme Court vacated the 9th Circuit’s judgment and remanded the case for application of the standard announced today.

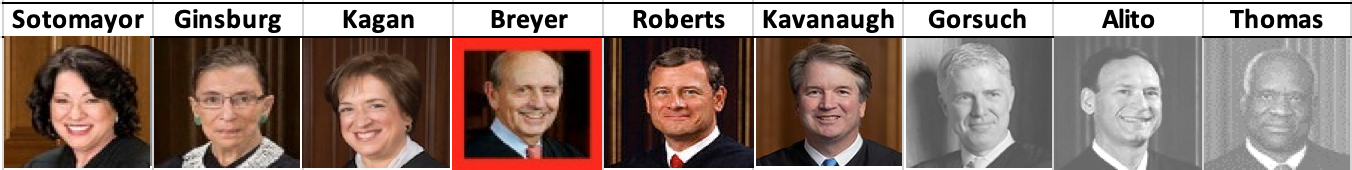

Perhaps the most striking feature of Justice Stephen Breyer’s opinion for the majority – which drew the votes of Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, as well as those of Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan – is its interpretive method. The opinion reads like something from a long-ago period of statutory interpretation, before statutory decisions regularly made the central meaning of complex laws turn on a single word or two and banished legislative purpose to the interpretive fringes.

Breyer put legislative purpose front and center in concluding that the interpretations offered by the County of Maui and the solicitor general would open a “large and obvious loophole in one of the key regulatory innovations of the Clean Water Act,” and allow “easy evasion of the [relevant] statutory provision’s basic purposes.” In describing the legal basis of the court’s ruling, Breyer twice placed the statute’s “purposes” as equal partners alongside “language” and “structure.” On this deeply textualist court, any reference to statutory purpose can draw a partial nonconcurrence, or even a dissent, from textualist justices. Today, however, Breyer’s invocation of legislative purpose – and even a brief discussion of legislative history! – went unchallenged by the five other justices who embraced his test for determining the reach of the Clean Water Act’s permitting requirement where discharges to groundwater are involved. (Kavanaugh joined the court’s opinion “in full,” but filed a concurring opinion mostly highlighting his agreement with Justice Antonin Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States, narrowly construing the “waters of the United States” protected by the Clean Water Act.)

Even Chevron deference, the doctrine requiring courts to defer to an administrative agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute – forcefully criticized by conservative justices in recent years and described by Breyer, amusingly circuitously, as “what the Court has referred to as Chevron deference” – made a brief appearance in the majority opinion. Breyer noted that “neither the Solicitor General nor any party” had asked the court to defer to the Environmental Protection Agency’s recent “Interpretive Statement,” which opined that all releases of pollutants to groundwater are categorically excluded from the Clean Water Act’s permitting program. “Even so,” Breyer went on, the court “often pay[s] particular attention to an agency’s views in light of the agency’s expertise in a given area, its knowledge gained through practical experience, and its familiarity with the interpretive demands of administrative need.” Here, however, Breyer explained, EPA’s interpretation was “neither persuasive nor reasonable,” given the escape hatch it would pry open in the Clean Water Act’s permitting provisions.

Once he had rejected, as “too extreme,” the alternative tests offered by the lower court, the litigants in the Supreme Court and his dissenting colleagues, it fell to Breyer to explain just what he meant by “the functional equivalent of a direct discharge” to navigable waters. He candidly acknowledged that his approach “does not, on its own, clearly explain how to deal with middle instances.” He offered a list of “just some of the factors that may prove relevant,” seven in all, including “transit time,” “distance traveled” and other facts about the journey of the pollution from a point source to the navigable waters. “Time and distance,” he emphasized, “will be the most important factors in most cases, but not necessarily every case.” In making these judgments, Breyer emphasized, “[t]he objective … will be to advance, in a manner consistent with the statute’s language, the statutory purposes that Congress sought to achieve.”

Breyer appeared optimistic that the courts, EPA and the states can administer the new test without too much difficulty. The courts, he noted, can “provide guidance through decisions in individual cases” – and even, “in an era of statutes,” make use of the “traditional common-law method, making decisions that provide examples that in turn lead to ever more refined principles.” EPA can “provide administrative guidance (within statutory boundaries),” through individual permits, general permits or general rules. EPA and the states can avoid the prospect of greatly expanded permitting requirements through various permitting techniques, and courts can apply the Clean Water Act’s penalty provision with sensitivity toward the reasonable expectations of those potentially ensnared by the court’s new permitting test.

What emerges from all this is a vision of Congress, the executive branch, the courts and the states working together to protect the waters of the United States while keeping the program within manageable bounds. In this way, too, perhaps, Breyer’s opinion is a happy throwback to earlier times.

Justice Clarence Thomas dissented, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, and Justice Samuel Alito issued his own dissent. Both dissents embraced the same test, requiring a permit only “when a point source discharges pollutants directly into navigable waters.” (This exact verbal formulation of the test appears in both dissents.) Thomas rested his argument on statutory text and structure, faulting the court for speculating about Congress’ intent: “Our job,” he reminded his colleagues, quoting from a recent opinion, “is to follow the text even if doing so will supposedly undercut a basic objective of the statute.”

Alito’s solo dissent is well summarized by his opening line: “If the Court is going to devise its own legal rules, instead of interpreting those enacted by Congress, it might at least adopt rules that can be applied with a modicum of consistency.”

Recommended Citation: Lisa Heinzerling, Opinion analysis: Opinion analysis: The justices’ purpose-full reading of the Clean Water Act, SCOTUSblog (Apr. 23, 2020, 7:09 PM), https://ift.tt/3532ggV

"Opinion" - Google News

April 24, 2020 at 06:09AM

https://ift.tt/3532ggV

Opinion analysis: Opinion analysis: The justices’ purpose-full reading of the Clean Water Act - SCOTUSblog

"Opinion" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2FkSo6m

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment