With an interest in generating accessible writings that makes the connection between the larger social and political landscape of the country and its performing arts more evident, this monthly column is an attempt to un-bracket the dance discourse from its contained category of “Arts for Art's sake”. Read more from the series here.

***

In an article following the murder of George Floyd, Thenmozhi Soundararajan points towards “white adjacency” as something that allows Asian minorities to be weaponised by the dominant whites to further the marginalisation of Black voices. White adjacency is when a person who is technically a minority, has access to, utilises and sometimes benefits from white privilege. Taking a critical look at the role that South Asians, especially Indians, play in the equation between the oppressed Black communities and the racist American state, she foregrounds instances such as the tying of rakhis to white cops and “Hindus in support of Trump” as blatant performances of white adjacency.

In the context of classical dance, white adjacency can take the form of indulging in self-orientalising behaviours, internalising the exotic gaze or even hiding caste privilege to benefit from one’s racial profiling. The birth of classical dance itself is an outcome of the collusion between white supremacy* and upper caste desire to be custodians of “Indian” culture. Two attributes of colonial rule — Victorian morality and the Oriental gaze — proved handy in the project of classicisation.

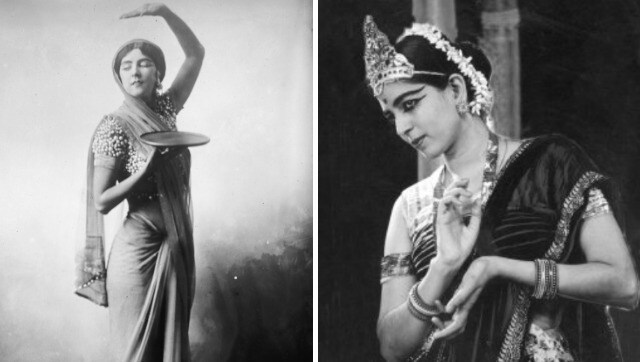

While Victorian morality gave the required conservative framework to justify the abolition of public dancing by women of hereditary dancing communities, the Oriental gaze contributed towards refashioning the tradition to suit the ideological and the aesthetic palate of the elite members of the upper caste communities. This refashioning involved reining in whatever was seen as excessive in the performance practices of the hereditary communities especially with respect to erotic expressions. One needs to only recall that it was in the nest of the deeply oriental Theosophical society that Bharatanatyam evolved to take its modern shape.

The collaboration between Rukmini Devi, (founder of the Kalakshetra institute) and Theosophical Society is symbolic of how the upper-caste position of classical dancers has afforded them an edge over lower-caste performing communities in their equation with the dominant white culture. Diasporic discourses that position classical dancers as cultural representatives of a racial minority often turn a blind eye towards their caste locations. For Arpita Bajpeyi, Kathak dancer and dance scholar based out of Canada, this is because, “First, caste privilege (like any privilege) makes it difficult to see when you benefit from it. Second, race is the pressing issue that frames how we understand our lives and selves in the global north. It means that the version of ‘Indian’ that you occupy in white spaces cannot capture the multitude of identities that make up ‘Indian’ or ‘South Asian’. This means that we represent ourselves as a more homogenised, hegemonic version of these identities.”

By virtue of being upper caste, many classical dancers who find themselves to be a racial minority in white dominant countries, are simultaneously the ones who have structurally benefited from the pervasive caste violence in the field of Indian classical dance in the last century.

There is enough scholarship at present to establish that Indian classical dance forms have been appropriated by the upper caste communities by systematically pushing the predecessors of these traditions — the isai vellalars, maharis, kalavantula, tawaifs — into the margins. This continues to reflect in the caste demography and in the aesthetic discourse persistent in the field today. The classical dance communities in diaspora are an extension of the same networks of privilege that dominate the field in India, there is also the same ever-present absence of caste discourses except with an added complication of race. The lack of caste diversity from almost all prominent international dance festivals is a testimony to how caste and class exclusive these spaces have been.

This is not an exercise to dismiss racial experiences of upper caste Indians or to negate that they would remain “outsiders” despite their caste privilege in a white country. Cultural gatherings such as dance festivals or dance classes can offer a space to collectively sigh in relief, to be uninhibitedly brown in white dominant countries. However, it is important to ask if being brown is enough for a person of a marginalised caste to let out the same sigh of relief.

In India, for instance, a lower caste Bharatanatyam student shared that she was labelled a “bad dancer” and though she had no words to express why, she was sure this had to do with being the only individual from that caste in her dance class. She felt her clothes were too “tacky” for her dance class or the lunch she carried for rehearsals smelt too pungent. Just like “ethnic” might be equated with “over the top” in white dominant countries, the aesthetics of lower caste traditions are considered “excessive”, “tacky” by the dominant aesthetic canons imposed in the field. With dancers in diaspora being the Brahmin elite, it is important to ask if the spaces they hold, aesthetics and body practices they promote, are truly caste inclusive.

It becomes imperative that classical dancers’ racial equation with the white majority is triangulated with their caste position so as to not participate in a culture of white adjacency, and occlude the experiences of the of the lower caste people in the field.

Cultural gatherings such as dance festivals or dance classes can offer a space to collectively sigh in relief, to be uninhibitedly brown in white dominant countries. Image for representation only. Getty Images/File Photo

A large number of classical dancers who run dance institutions in the US migrated post-1965 on dependent visas, as wives of doctors and engineers (Srinivasan 2012, 38). They stand on the shoulders of the many Black people who lobbied during the Civil Rights Movement to open up the American borders to people of colour. It is under the pressure of the Civil Rights Movement that the US government decided to open its borders to Indians and other Asians, albeit to the educated minority only, who now constitute the “model minority”.

The history of Brahmin appropriation of hereditary traditions in India on the one hand and the Civil Rights Movement pushing for racially inclusive societies in white dominant countries on the other, have been critical in laying the ground work for classical dance in diasporic contexts.

In her work exploring the histories of Indian dancers who migrated to the US in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Priya Srinivasan argues that the contributions of the labouring Indian bodies (people from lower castes) are written out of the dominant cultural history of dance in America. She critiques especially the popular biographical narrative of Ruth St. Denis — known as the pioneer of American Modern Dance — by proposing that Denis used her inspirational encounters and interactions with nachwalis to build a career for herself as an Oriental dancer while not acknowledging their contributions.

Unlike nachwalis or women from hereditary castes, Brahmin dancers today occupy a more visible place in the diaspora. When classical dancers in the diaspora project themselves as cultural representatives of an appropriated tradition, in a first world context, how many such contributions of hereditary dancers are they erasing? This is not dissimilar from the question that needs to be asked in India. But shared racial identity cannot subsume caste differentials, and without acknowledging these differences, it is not possible to leverage one’s privilege to build solidarities which are truly inter-caste in nature.

Notes —

*Colonial rule is an instance of white supremacy because of its assumption that the white race is morally, intellectually and genetically more superior to the colonised.

*Nautch women have a history in the United States, and the Coney Island nautch dancers were not an anomaly. An unusually high number of Indian dancers were brought from Bombay to Coney Island by Thompson and Dundy in 1904. Simultaneously, PT Barnum brought another group of dancers from South India and Sri Lanka for his New York shows, and another troupe from Sri Lanka were brought to the St. Louis World Exposition. (Srinivasan 2012, 69)

References —

Srinivasan, Priya. Sweating saris: Indian dance as transnational labour. Temple University Press, 2011.

Updated Date: Jun 25, 2020 09:38:29 IST

"discourse" - Google News

June 25, 2020 at 11:08AM

https://ift.tt/2A5XlRA

A robust caste discourse in Indian diaspora's classical dance practices is vital — and overdue - Firstpost

"discourse" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KZL2bm

https://ift.tt/2z7DUH4

No comments:

Post a Comment