Exclusive

Exclusive

China is focusing on 'discourse power'. Shore up defences

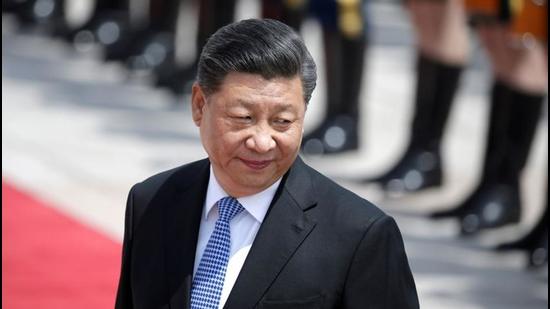

In China’s strategic lexicon, might is right but might is essential to earn the “right to speak”. President Xi Jinping’s messaging both to Chinese citizens and the world, as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrated its march to the next century, seemed to stress on this theme repeatedly. Aside from the obvious deification of the Xi era and CCP, if one breaks down the centenary’s themes to, say, bumper stickers, the following would sum it up — we have arrived; we will not be bullied; the party is always right/the party is forever.

In Chinese frameworks, a country’s huayuquan or right to speak or the power/authority to speak is essentially a form of power equivalent to military and economic power, “with discourse as its carrier”. Yet, for all of China’s gains in hard power and material strength, it has always felt lacking in “discourse power” relative to the West.

So, China has invested heavily in telling “an overwhelmingly positive” story of its history. Purged of failures, this history credits the party for China’s strides and leading the Chinese people “from one victory to another on an unstoppable march towards national rejuvenation”. This narrative is essential to maintaining the infallibility of the party-State and is seen as central to its domestic legitimacy.

But Xi has also wanted China’s discourse power to resonate externally — China’s story, on China’s terms, and Chinese ideas setting the global agenda. From the 19th party congress in 2017 onwards, Xi has consistently demanded that Chinese discourse power underwrite the promotion of the “China model”, and project its ability to “influence global values, governance, and even day-to-day discussions on the world stage”.

Also Read | ‘Stop demonising us,’ China plays victim as US calls out Chinese aggression

Within China’s borders, discourse power is a potent tool of the State, but when expanded to the international system, there are serious long-term repercussions. The emphasis here is not on dialogue, but on the “contestation of ideas” which have underwritten widely accepted universal values and norms, institutions and governance models. There is no space for reform or consensus in this narrative. It is about proving that all prior methods for solving the world’s problems have failed while China offers one with better solutions which it has applied successfully domestically.

China’s discourse power represents the party-State as the righteous leader in the international space. Concepts such as a “community of shared future”, Made in China 2025’s goal of dominating global science and tech, and the creation of international financial institutions aim to project the ability to deliver an alternative solution to global needs. With a military budget of $209 billion, and massive investments in the grand Belt and Road Initiative as well the Health Silk Route, China’s national rejuvenation is showcased as adding value to global governance.

However, beyond persuasion, Chinese discourse power is all about the power to prevail across the diplomatic, economic, military, cyber and technological domains. It has manifested itself in the People’s Liberation Army tactics of information warfare across the spectrum, including on the China-United States (US) split, Taiwan, aggression in the South China Sea, technology wars and deflection on the Covid-19 crisis.

For India, this has been especially visible vis-a-vis the contentious border dispute. New Delhi has understood that China will leave no stone unturned to show that it was on the right side of history, given the emphasis the CCP’s centenary celebrations have placed on “correct” versions of its deemed successes.

Yet, looking at China’s efforts from a narrow propaganda lens would be a folly — for the stakes for India are much higher, more nuanced and across multiple domains.

Also Read | The vaccination drive is entering a challenging phase. Change strategies

First, India is an open society where Chinese officials have always had the opportunity to push their narrative in a vibrant and noisy media environment. Often, there is no reciprocity given the absence of a level-playing field on the Chinese side as they wield an iron fist with their State-controlled information flow. This awareness is yet to be internalised in India and requires constant calling out.

Two, unlike earlier perceptions that India does not occupy mindspace in China, Galwan proved Beijing’s India policy is not monolithic. Scholarship has highlighted a trend of growing antagonism and a pessimistic outlook regarding the future of India-China relations. An enduring portrayal of “an obstructionist India”, an inevitable rivalry, “successor of a colonial order”, “hegemon with a Monroeist doctrine towards South Asia” and “peddling the US-Indo Pacific Strategy” have taken root and are important markers of China’s framing.

Three, when China speaks of dominating the information domain, it also means supremacy over the electronic and cyber domain. Reports of repeated cyber attacks on India’s critical infrastructure, including in the banking, defence and the financial sector, and the high-profile alleged targeting of the Maharashtra electricity grid during the ongoing boundary crisis are not coincidences.

Four, despite India maintaining that it can no longer delink peace and tranquillity on the border from other aspects of the relationship, China’s insistence of compartmentalising the relationship while keeping multiple fronts on the Line of Actual Control alive exemplifies coercive tactics. China’s psy-ops over “Arunachal Pradesh’s slow pace of development” in comparison to the development of model villages and the first electric train close to the border on its side, and publicising the decision to build a controversial multi-billion dollar hydropower dam on the Brahmaputra river in Tibet, are all par for the course.

Finally for India, while managing the China relationship will be guided by its policy of building its internal capacity, diversifying and leveraging external partnerships and keeping channels of dialogue open, the CCP’s show of strength is also a reminder to heed to advice of practitioners and invest in capabilities to understand China better. From language training to understanding what the CCP’s ‘weapon of influence’ United Front Work Department (UFWD), can do to affect Indian interests, we need to dig deep.

China’s discourse politics will target multiple fault lines in India. To prevail, New Delhi must create awareness and shore up its defences to push back against the renewed Chinese ambition to dominate mind games and project its power.

Shruti Pandalai is a Fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses

The views expressed are personal

Please sign in to continue reading

- Get access to exclusive articles, newsletters, alerts and recommendations

- Read, share and save articles of enduring value

-

Anand Mahindra’s latest share features an ‘exquisitely beautiful’ bird. Watch

-

Doggo meets human friend after 10 months, her reaction is priceless. Watch

-

Sachin Tendulkar shares clip of man playing carrom with feet. Watch

-

Someone added ‘googling’ as a skill on CV, landed an interview. See viral tweet

"discourse" - Google News

July 27, 2021 at 04:55PM

https://ift.tt/2WeXL2z

China is focusing on 'discourse power'. Shore up defences - Hindustan Times

"discourse" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KZL2bm

https://ift.tt/2z7DUH4

No comments:

Post a Comment