There is no gainsaying the fact that the figure of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has emerged as the most significant talking point in Indian politics. Now that the Election Commission has set the dates for the five assembly elections, one can only expect the obsession of India’s political commentators and campaign managers with Modi to grow, and the process of showcasing his persona as the epitome of all that is good, or evil, in the current politics of the vast country to be speeded up. The point that the critics and acolytes of the prime minister miss is the harm that the narrowing down of the political agenda to just one person does to the larger interests of the country and its bustling, resilient democracy.

This poverty of public discourse about the nature and content of politics in India with its rich, classical tradition in political theory, vigorous political debates during the long-drawn-out freedom movement, its continuation in the Constituent Assembly debates, and in parliamentary debates during the early decades after Independence, is astounding. Had agenda-setting not been as important as it is for the critical decades ahead, all the Modi-bashing of the political class and the cartoons around his theatricality, would have provided some comic relief during these dark days of the pandemic. But the stakes are much too high not to take notice of what gets left out of political discourse thanks to the obsession with Modi, to the point of merchandising his personal security, in the ruthless game of political upmanship.

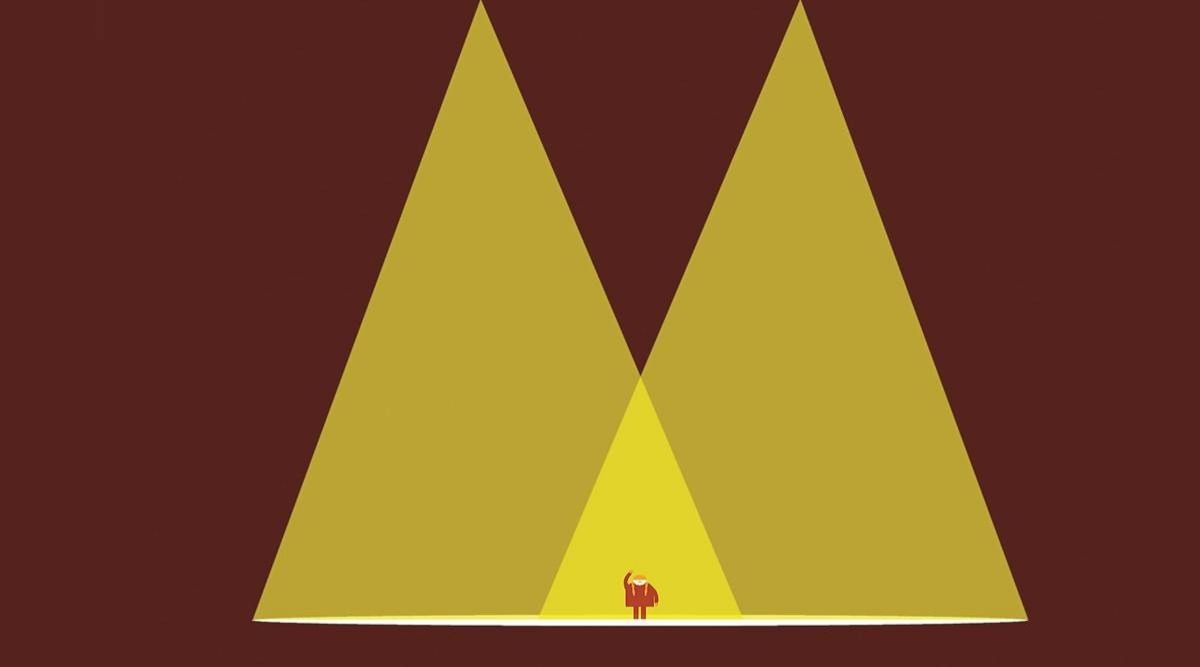

How has this fixation with Modi and the reduction of the full range of politics entirely to his persona come about? To this question, there are two possible answers. The images of a “saintly” Modi taking a holy dip in the Ganges, widely diffused by TV channels, would lead cultural anthropologists to take a cue from Clifford Geertz in pointing to the causal link of pomp and theatricality with state power. The second answer, going back all the way to Marx, would argue more about the political acumen of a talented leader, exploiting a structural flaw to cast himself as the embodiment of popular aspiration and will. “Man makes history, within conditions imposed by history”. Both insights help explain the emergence of Modi as the focal point of Indian politics, much like the parallel rise, quite ironically, of Gandhi and Churchill — in their deft use of language, metaphor, accoutrements, and theatricality — to the pinnacles of public visibility during the last decades of the freedom movement.

Deconstruction of Modi’s rise reveals the adroit manner in which he has encapsulated three strands of the deeper layers of Indian politics — the stalled process of state formation, a deep collective anxiety about where to place medieval history within the structure of the present, and, of course, state subsidised welfare such as cooking gas, micro-bank-accounts, toilets, infrastructure and so on. An analysis of the outcomes of the two parliamentary elections of 2014 and 2019 and the assembly elections in between, shows how neatly the electoral performance of the BJP follows the combination of the three strands. The most spectacular demonstration of the vulnerability of a Modi-centric campaign was seen in West Bengal, where the region has found its own mode of integrating Islam within its political culture and the tap of welfare was firmly in the grip of Mamata Banerjee — the local supremo and an equally deft politician in the mirror-image of the prime minister.

Shifting the focus away from Modi as the single issue will help bring public attention back to the structural parameters of Indian politics that get scant attention today. Not doing so will have grave, unintended consequences.

As things stand, a Modi win signals the continuation of his symbolic acts such as cow worship — it skips any analysis of the proper role of the cow in the agricultural value chain. A Modi defeat reinforces the tendency to “let sleeping issues lie” and skip over stalled processes of territorial integration, reform in key sectors of agriculture and integration with the global market economy, or even deeper and more conflictual issues of citizenship and national identity. In brief, with a single-issue election, India loses, whether Modi wins or concedes defeat.

Lest we forget, a Modi-centric electoral discourse skirts around the biggest conundrum of the politics of transitional societies: Can electoral democracy replace revolution? Elections — however free and fair — can only process politics “within the system”, but are not any good at tackling the “politics of the system”. Elections produce mandates that promise structural changes in the economy and society, but the hardship that they entail for key sections of the electorate stymie their implementation. Caught in a “middle democracy trap”, India is likely to go through cycles of “maintaining” elections that focus on the rewards of office, alternating with “transforming” elections that promise basic structural changes. By bringing the larger agenda of politics back in again, one would be able to prepare the electorate for the rough ride ahead as the next electoral cycle sets in, instead of their panicking about democratic “backsliding”.

Mitra is an emeritus professor of political science at Heidelberg University. His The 2019 Parliamentary Elections in India: Democracy at Crossroads? jointly edited with Rekha Saxena and Pampa Mukherjee, will be published by Routledge, later this year

"discourse" - Google News

January 14, 2022 at 05:30AM

https://ift.tt/3I4BHdS

The problem with Modi-centric discourse in Indian politics - The Indian Express

"discourse" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KZL2bm

https://ift.tt/2z7DUH4

No comments:

Post a Comment